|

Voting in general (or federal) and local elections is a topic which is becoming increasingly important with elections in the US and UK set to take place this year (date for UK election TBC). With these elections coming up anarchists and other leftists must decide if voting should be used as a means for change, within Marxist and anarchist circles there are varying opinions on the viability of electoral politics to achieve favourable conditions for the working class to operate in. I like many others would reject voting and participation in electoral politics as a viable means to achieve socialism, historical anarchist theory and practice have made this abundantly clear and we as modern anarchists should continue to abide by our principles. Voting in elections within liberal (or illiberal) democracies is the main way through which the ruling class provides the illusion of representation and choice. We are told that only through voting for a representative can we achieve the changes we want to improve our livelihoods and opportunities, with election cycles often taking place every five years (or four) the governments of today have achieved a remarkable amount of success in channeling the frustration of voters into a repetitive cycle of voting for your next oppressor. This is not to say that living within a liberal democracy is the worst form of government to live under, no anarchist will tell you that living under an absolute monarchy or fascistic regime is preferable to living in a liberal democracy. Rather than embracing the kindness of the ruling class who give workers the privilege of voting for their next oppressor, anarchists would argue that parliament and other democratic institutions are products of the ruling class to reinforce their interests backed by organised violence to enforce the will of the so-called people’s representatives or MPs. Because this system was created by and ruled by the capitalist class, any attempt by workers to vote themselves in and subsequently socialism in through the ballot box will inevitably fail, by participating within the system so-called socialist MPs or representatives present the ruling class with an option to reinforce their position by offering small concessions which present no harm to their power but can be presented as heroic victories on the road to socialism by those so-called socialist MPs. Before long those who become voted into the system thinking of change become those fighting tooth and nail to defend the status quo. Historical anarchy: To fully understand this critique it is necessary to understand the distinction between the state and government, the state within anarchist theory is the collection of permanent institutions which have entrenched power structures and interests whereas the government is the collection of representative politicians who represent the people within the state. The clear distinction here is the lack of permanence that democratic representatives have compared to the established institutions in the state whose permanence allows them to continually reinforce and build on the interests of the capitalist class1. Historical anarchists through their extensive writings at the time developed and built on the ideas of anarchism established in the first international (or international working men’s association). Theorists ranging from Proudhon to Malatesta to Goldman wrote extensively on the topic of democracy, however, anarchists’ critique of democracy is underpinned by the anarchist analysis of authority and its understanding of the state (outlined above). Lucy Parsons within her text “The Ballot Humbug” (1905)2 plainly outlines what anarchists believe about the authority of men: “It is better to have majority rule [...] than to have minority rule which is only in the interest of the few [...]. But the principle of rulership is in itself wrong; no man has any right to rule another man.” To reject the principle of rulership thereby forming the basis for the rejection of the liberal understanding of democracy. Alongside this rejection of leadership, several anarchists developed critiques of moderate state socialists (those who believed that winning elections alongside measures of direct action could be used to transform the bourgeois state into an instrument for the development of socialism). Contemporary anarchist historian Zoe Baker3 synthesises the anarchist critiques of parliamentarianism and electoralism into four distinct points. Firstly, anarchists critiqued the moderate state socialists for having the belief that state power could be captured peacefully through a primary focus on winning elections. Both radical Marxists and Anarchists accepted that ruling capitalist classes would not allow a socialist parliamentary majority to vote away their privileges through legislative means simply. This in turn meant the only way to overthrow capitalism was instead through a working-class social revolution, details on the outcomes of this social revolution differed between both groups. Secondly, anarchists understood and rejected the idea that immediate improvements in conditions could be won through passing legislation e.g. the eight-hour workday. When legislation becomes law within liberal democracies there often lacks mechanisms to force capitalists to institute the requirements outlined in laws, instead, workers themselves through direction such as strikes often force the implementation of laws through their means. In addition to this, moderate state socialists who argued for a combination of both electoralism and direct action were bound to create a contradiction, most state socialists would have argued for electing socialists to parliament while placing pressure on liberal politicians from below through various means such as socialist press, strikes and demonstrations. However, the inevitable outcome of this process (in theory) is a socialist majority in parliament which would continually be pressured by the same working class they were elected to represent. This therefore would be pointless. Although there was no unanimous agreement about the exact form of anarchist organisation many currents such as anarcho-syndicalism argued for winning immediate improvements through strike action as argued by Rudolf Rocker4. Thirdly, anarchists critiqued electoralism because of the dangerous habits that it makes working people practice. By participating in elections, anarchists argued that workers would develop counter-revolutionary traits such as believing that change will come from above and thereby waiting for elections to make change. Instead, anarchists due to their belief in the unity of means and ends believe that by participating in direct action workers will develop mental faculties which allow them to contribute to the self-liberation of the working class through the social revolution. Finally, anarchists unlike moderate state socialists argued that any group entering the state no matter their intentions end up slowly diluting their beliefs and convictions due to the nature of the system reflecting the interests of the bourgeoisie. The seizing of state power via democratic means would therefore require the leadership of any socialist party to administer the economy and state in the same ways that the prior capitalists did, which in turn leads to a gulf between the newly elected socialists and the working class who would not see immediate benefits from the rise of socialists to the top of the political pyramid. Many nations experienced the state socialist decline into capitalist management, France for example had multiple socialist ministers enter the cabinet only to utilise the organised violence of the state to hamper the direct action of unions and working-class organisers during periods of labour unrest. 5 Meanwhile in Germany and Britain, their respective socialist/social democratic parties rallied to their imperialist governments during 1914 which saw them completely abandon any pretense of working-class internationalism. 6 The British political establishment: Bourgeois democracy in Britain has an extensive history spanning back several hundred years, with the rise of industrial capitalism within the 18th and 19th centuries the old system of parliament used by the aristocrats to govern was suddenly under pressure from the new middle class to grant them representation within the lords and commons. Several acts of parliament followed which pushed through a long process of suffrage extension starting with industrial capitalists and ending with universal suffrage for all workers in 1928. Throughout this time several thoughts emerged among socialist circles in Britain about using this emerging system as a means through which positive change for the workers could be made, the main articulation of this emerging belief in reformism came through the founding of the Labour Party in the early 20th century who emerged through a growing desire for working class and union representation in parliament which the establishment Liberal party could not provide. Since the Labour Party’s first entry into government in 1914 they have been responsible and complicit within the British political establishment and its efforts to stem workers’ action in the economic sphere. Under the post-war consensus, Labour championed Keynesian economics (full employment and welfare development) as a method by which capitalism could be restructured to be more humane but also keep the workers in good health to continue high levels of productivity. The flip side of this however was a continuing opposition to any working-class action which threatened the establishment both before and after the Second World War, whether this be crushing strikes using Tory legislation or cutting workers’ pay in times of recession the Labour Party and its affiliated trade unions have in many ways been the oppressors of the very people it has in the past claimed to represent. As the Labour Party became more and more entrenched within the capitalist system it gradually moved towards shedding any pretense of “socialism”, by the mid-1990s Labour had fully dropped any commitment to any policy outside of collaborating with and managing the affairs of capital, this largely came after workers in the 1970s-1980s began banging on the limits of capitalism which prompted the Thatcherite neoliberal counter-revolution. Some may argue the removal of clause four is what marked this transition while others may point elsewhere - Regardless of this debate in the 21st century, we can all but confirm that a labour vote is a vote for capital. Between the 1990s and the early 2020s the role of political parties and voting has stayed largely the same with voters once again trudging to the voting booth to elect or reelect capital’s newest puppets, during this time labour militancy was at an all-time low with both parties (Labour and Tories) presenting the workers with acceptable standards of living for the middle class while the TUC unions kept the lid on what little working-class anger there was left in Britain. Where does this leave us today? With an election cycle upcoming and the Tories looking like they are on the way out of parliament what should we as anarchists do? 7 Activity paralysis: During election time it seems to be the case that the media, party activists, social media and workplaces all stop their activities to focus on the election. Whether this is attending hustings, door knocking, watching debates or voting itself, life outside of elections seems to stop. This is a phenomenon we must break, the changing of capital representatives from one to another does not change the fact that workplace struggles, organising and demonstrating will go on. Our focus cannot become clouded by engaging with middle-class liberals in their political sphere, life will go on even if you decide to vote for the most radical candidate in the election (Green, Workers Party, TUSC etc) Those left-wing political parties like the Greens, Workers Party and TUSC (Trade Union and Socialist Coalition) fail to understand that the resources spent on mobilising activists and campaigning are all for nought. Take for example the UK Green Party’s aim to elect four MPs to parliament at the expense of Labour and the Tories. Out of the 650 MPs elected to the commons, the maximum influence the Greens could have on policy decisions is at best negligible, by sending their party leadership to Westminster the gulf between party members and leaders becomes ever wider. As we have seen with other parties, this will allow the Greens to take their rightfully earned place as mediators between capital and the working class. The French Popular Front government of 1936 provides an excellent example of an incoming socialist government immediately repressing workers’ strikes to restore stability in 1936-19388. Even if we were to believe that a radical left-wing party were to win a majority in the election there are several countermeasures the state and capital will take to ensure its downfall. The reaction of the markets is often the first to strike, after the government whether left or right announces a policy that the markets do not like the value of stocks will plummet thereby signalling the masters of capital want a reverse in policy which almost always occurs (As seen by the fall of the Truss government). 9 Secondly, the incoming government could pursue a policy of banning capital from fleeing thereby isolating the government from further capital investment which leads to economic collapse and a sharp decline in living standards as seen in the Cuban state capitalist project. Thirdly when all else fails, the mask of liberal democracy falls to pave the way for a capitalist counter-revolution in the form of fascism which represents capitalism in its purest form - barbarism. Realistically if you as an anarchist live in an area where a candidate like Jeremy Corbyn or a Green Party candidate is likely to win then the harm in voting is minimal, the act of voting becomes harmful when it is adopted as the primary method used to achieve social change. Anarchists as far back as 1869 rejected this as a strategy, to adopt electioneering as a strategy for social change and improvements in conditions would be a betrayal of our ideals and principles. Contrast this to the organising that we in the anarchist scene can pursue, pouring time into local, regional and national struggles for a better future for the working class is where our time must lie. Anarchists place major importance on the self-liberation of the working class, by using direct action workers can reclaim individual capacities such as initiative, solidarity and creativity when it comes to solving problems of their own. Not only does direct action restore workers’ capacity to act for themselves and their collective interests but direct action allows for the prefiguring of our future society within our current society. When the revolution happens we will not find an army of workers premade for the revolution, only through exercising our mental faculties can we build towards libertarian communism. This is not a phenomenon that electoralism can achieve, the emancipation of the workers is not compatible with voting for your next oppressor to do it for you. Those who still have faith in electoralism could present several reasons why voting is a necessary thing to do, within the US democrats or liberals will often make a fuss about rallying behind one evil to stop another (Biden > Trump) thereby making the argument that under a democratic president, the working class are more likely to win favourable concessions as well as radicalise more people towards socialism (often through failed campaigns like those of Bernie Sanders). 10 From the past to the future: The lesser of two evils idea has become increasingly prominent within US politics as the stage is set for Trump to take on Biden for the presidency, many on the center left are engaging in a rally to the flag mentality concerning the democrats. The argument goes as follows, if center-left democratic socialists do not vote for Biden then Trump will win the presidency and everyone will suffer more than under Joe Biden. It is not exactly contested on the left about who is the better candidate between Trump and Biden, it is important to consider however the allocation of resources, time and faith in the system11. As well as this, voting for the lesser of two evils is often regarded as damage control as even some on the center-left recognise the glaring similarities between the Republicans and Democrats. Naturally, however, every election cycle the Republicans or Tories or CDU-CSU will summon a candidate who the centrists deem as the next reincarnation of the devil and therefore once again we must all rally behind the least worst candidate (Biden, Starmer, Scholtz etc). At what point however does defeating the bigger evil turn into a repetitive process of voting time and time again for bourgeoisie politicians? A further issue related to this point is that when discussing electoral politics by placing support behind an individual candidate or party you create the impression that the system itself is not the issue, instead it is merely an issue of who occupies the system. It is particularly easy to point out the flaws of a capitalist, pro-business politician by looking into their voting records and money received from various lobbying organisations12, this provides great ammunition for aspiring opposition politicians who can use this same information to argue that if only they were in that position they could do better for their constituents. As mentioned before, the issue with electoralism is the system itself. Regardless of who enters the system whether they be a liberal environmentalist, a community activist or a socialist the power relations and structure of the system are designed to transform those who enter into statesmen who become more concerned with reproducing their power rather than pushing for radical social change. From a local to a national level, liberal democratic systems of governance have a remarkable prowess at watering down the radicalism of elected politicians. It is a common story of radical politicians campaigning on radical policies including healthcare expansion, nationalisation or increasing the minimum wage. Grandiose promises like these are a fantastic magnet for attracting voters to a politician’s cause, Obama I would argue is the best example for this argument. The policy of Obamacare proved popular enough to propel him to the White house in 2008, the congressional system however and its extensive association with lobbyists and business interests proved more than capable of slashing the original proposal down to a palatable enough reform for both the business elites and Obama himself who took his watered down win and used it to secure another term in the halls of power. The role of these democratic institutions therefore is not to provide an avenue for change, these institutions serve as a distraction through which radicalism can be assimilated and eliminated to preserve the integrity of the system at large. No matter if you vote or not your conditions at work, at home and in your community will not change no matter which scumbag sits in parliament on your behalf. 13 Is direct action compatible with electoralism?: Inevitably there will always be some who advocate for the dual approach of doing both participating in elections as well as conducting direct action in the workplace and wider society. Anarchists (once again) reject this outright. Although voting for the most progressive candidate poses no real threat to anarchists the idea that we can do both strategies with equal vigor is, as we have established the nature of the electoral system is hierarchical but this also extends to the campaigns which prospective politicians conduct to be elected to office. Contrary to what some on the left may tell you, electoral campaigns are not a way through which we can encourage equal and mass participation. To illustrate this take the example of the UK Green Party14, within its political party programme the MP for Brighton Pavilion Caroline Lucas says: “What’s special about the political programme is that it’s the culmination of a grassroots democratic exercise. Our policy is set by our members - meaning that our leaders have no more voting power than our newest recruits - and the breadth of these transformative ideas reflects just how lucky we are to have such a dynamic membership.”15 In their political party programme the idea of mass and equal participation seems to be prominent and at the forefront of the Green Party Campaign. But is this reflected in the Green Parties election campaign? Quite quickly you can see that it is not, the Green Party’s “Four for 24” campaign illustrates the hierarchical nature of their campaign through their desire to concentrate support and attention around the four politicians with the best chances of securing power at the next election. This phenomenon of hierarchical electoral campaigns is not unique to the Greens however, the nature of electoralism requires each campaign to have one face, a leader to be the center of the campaign within the media which requires everyone else (voters, party activists etc) to be the followers who delegate their authority to this leader16 Within the US despite growing opposition to Biden within the democratic caucus through voting for uncommitted in party ballots (organised by pro Palestinian mass action groups) the effect has largely been minimal. Biden nonetheless still swept the nomination, it is interesting to think about what could have been achieved in Michigan if this effort and organisation could have been put towards a direct action project17 The governments of today through legislation have achieved remarkable success in exporting this model of delegating authority to other aspects of our society, the trade unions in Britain for example having been so restricted by the countless anti union acts of parliament are plagued by issues of bureaucrats suffocating rank and file militant action. The downturn in wildcat strikes and rank and file action can in part be attributed to the fact increasing amounts of power is being concentrated in the hands of union officials whose interests are in fact with the employers not the workers! Delegation of power to another and direct action are polar opposites, there is simply no way for people to both simultaneously develop ideas of solidarity and mutual aid while also participating in a hierarchical system of governance. To best make change and build towards our future society we cannot rely time and time again on prospective politicians who seek to slightly lessen our suffering, whether you organise a strike, a campaign or a reading group doing any form of direct action remains a better and more promising method of change rather than trudging back to the voting booth. What is to be done: If we in the anarchist scene recognise the ploy of electoralism and the infallible control of bureaucrats and capitalists over the state then what should we do? To put it simply - organise! By breaking the cycle of elections and educating workers on the pointlessness of voting we can contribute towards the development of new forms of social organisation based on the self-emancipation of the working class through direct action, solidarity and mutual aid. We know capitalism is not invincible, we know the ruling class will do everything they can to stem the direct action of workers - This is a sign to push forward even more, towards a new society - Anarchist Communism. This is by no means an easy task, but a necessary one if we are to continue the ongoing struggle against the twin evils of the state and capitalism. 1 The Anarchist FAQ, section J.2.2, https://anarchistfaq.org/afaq/sectionJ.html#secj21 2 The Ballot Humbug by Lucy Parsons (1905) https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/lucy-e-parsons-the-ballot-humbug 3 Means and Ends, The Revolutionary Practice of Anarchism in Europe and the United States by Zoe Baker (2023). Pp 143-153, available via AK press. 4 Anarcho-Syndicalism: Theory and Practice by Rudolf Rocker (1938), Chapter 5 “The Methods of Anarcho-Syndicalism”, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/rudolf-rocker-anarchosyndicalism#toc5 5 Syndicalism in France: A Study of Ideas by Jeremy Jennings (1990), pg 36. https://archive.org/details/syndicalisminfra0000jenn/page/36/mode/2up 6 “Don’t be a slave”, International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam) 7 “Abstention is the anarchist vote”, International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam), https://hdl.handle.net/10622/N30051001994398?locatt=view:level3 8 Workers Against Work Labor in Paris and Barcelona During the Popular Fronts by Michael Seidman, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/michael-seidman-workers-against-work 9 https://theconversation.com/liz-truss-resigns-as-prime-minister-the-five-causes-of-her-downfall-explained-192979 10 “Non Votate!", International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam), 11 ‘It will be the end of democracy: Bernie Sanders on what happens if Trump wins - and how to stop him by Ed Pilkington (2024 )https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/jan/13/end-of-democracy-bernie-sanders-on-if-trump-wins-and-how-to-stop-him 12 https://www.statista.com/topics/11840/lobbying-in-the-us/#topicOverview 13 “Elections? … Abstention!”, International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam), https://hdl.handle.net/10622/N30051001649281?locatt=view:level3. 14 https://www.greenparty.org.uk/ 15 https://greenparty.org.uk/political-programme.html 16 Direct Action Gets The Goods - But How? by Gregor Kerr (2007), https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/gregor-kerr-direct-action-gets-the-goods-but-how 17 https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/critics-bidens-handling-israel-hamas-war-push-protest-vote-michigan-pr-rcna140395

0 Comments

Socialist Appeal is the British section of the International Marxist Tendency (1), founded in 1992 after its leaders were kicked out of the Militant Tendency which later went on to become the Socialist Party. The group’s founders Ted Grant and Alan Woods were committed to the idea of entryism which saw Socialist Appeal continue to advocate for its members to join and agitate within the Labour Party as its Marxist voice. Since the election of Starmer as leader of the Labour Party, Socialist Appeal and Momentum members have been purged from the party in an attempt to end the Labour Party’s left-wing agitation (2). This seems to have ended Socialist Appeal’s naive belief in entryism and the seizure of state power through electoral means like Jeremy Corbyn’s election campaigns.

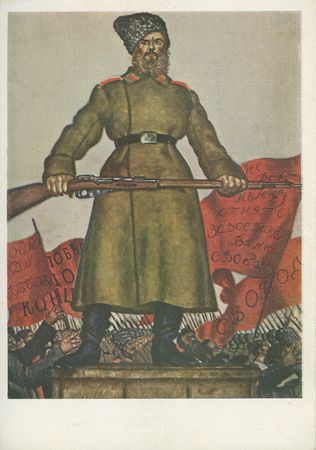

After 2013 Socialist Appeal began a campaign to enlarge its membership through the establishment of Marxist Societies on university campuses which saw its membership and profile on the left rise as many students joined the group due to its publicity and recent campaigns pushing for students to get organised. This has culminated in the announcement of the founding of a new “Revolutionary Communist Party” in 2024 which joins the list of previous Revolutionary Communist Parties dating back to 1944. Like other Leninist groups in the UK, Socialist Appeal is committed to promoting the ideas of figures like Lenin, Trotsky, and Marx via newspapers and meetings designed to educate and promote the idea of revolution among the working class and students. Their meetings usually start with a lead-off from a party member on a topic before opening up to wider discussion, Socialist Appeal often attends protests and has even imitated the SWP’s flagship Marxist event in late 2023 (3). Anarchists however should not be fooled. As with all Leninist revolutionary groups and parties, these groups do not speak or act in the interest of the working class. Although their propaganda will argue that they aim to educate the workers to prepare for the revolution, this is hardly the case which we can illustrate through analysis of their shallow propaganda and methods. The programme of Socialist Appeal first starts with a list of reformist demands to address British capitalism including a £20 minimum wage and the nationalisation of the top 100 companies as examples of immediate improvements for the working class, this then leads them to argue for a “Socialist Federation of Britain” as part of a “World Socialist Federation” (4) to be achieved by a revolution led by the revolutionary workers party. No clearer is Socialist Appeal’s naive world/historical view than articulated in A. Kramer’s article for Socialist Appeals magazine “Kronstadt: Trotsky was right! New material from Soviet archives confirms the Bolsheviks’ position” (5). This article aims to prove the innocence of key Bolshevik figures concerning their massacre of Kronstadt rebels who rose in 1921 to demand the end of Bolshevik authoritarianism and a return to workers’ control which was briefly practised in 1917 by workers shortly after the February revolution as outlined by Maurice Brinton who shows the acceptance of workers’ control by Lenin in 1917 (6). This SA (7) article grossly misrepresents both the Bolshevik response and reasons for the rebellion in a classic act of Bolshevik apologism. “in the naval base of Kronstadt near Petrograd, there was an attempt at a military coup against the Soviet government. The critical state that the Soviet Union was passing through in that moment meant that Lenin and Trotsky were forced to deal with the rebels very quickly” The Kronstadt rebellion contrary to what this article portrays, was by no means a military coup. The countless observers and accounts of the rebellion present a very different picture, the origins of the rebellion lay with a series of strikes which emerged as a result of the dismal winter conditions which workers faced in Petrograd which included a lack of winter clothing and minimal resources to use in industry largely due to the continuation of war communism after the end of the civil war. As Alexander Berkman outlines it was the “Trubotchny millworkers” who began striking, initially the strikes lacked political motives with initial action being solely to address the lack of winter clothing and supplies which paralysed industry in Petrograd. Rather than addressing the issues by loosening government control on industry and labour, the reaction of Trotsky, and Zinoviev was to denounce the strikes and resort to violent suppression when return to work did not occur, ironically this strategy backfired and heavily informed the opinions of the Kronstadt sailors. As a response to the strikes, the Kronstadt sailors sent a delegation to Petrograd to observe and report on the situation which naturally led to sympathy with striking workers, the following 16,000-man public meeting held in Kronstadt (also attended by Bolshevik leader Kalinin) did not fundamentally oppose the Soviet system. It did however condemn Soviet bureaucracy and methods used to suppress strikes by workers. A declaration was made shortly after the arrest of Kalinin who denounced the workers before him, this event set in motion the eventual crushing of Kronstadt by the Bolsheviks who could not stomach giving up party dictatorship and returning to the Soviet system practised in early 1917. The following response from Soviet officials to the strikes and Kronstadt with simple and clear, Berkman wrote as follows “An official manifesto appeared today. It is signed by Lenin and Trotsky and declares Kronstadt guilty of mutiny (myatezh). The demand of the sailors for free Soviets is denounced as “a counter-revolutionary conspiracy against the proletarian Republic.” Further misleading claims about the nature of Kronstadt are littered throughout the article. “These were not mere words. The real command over the rebels was concentrated not in the Kronstadt Soviet, as some naive individuals may think, but in the so-called “Court for the Defence of Kronstadt Fortress” (Paragraph 17), Bolshevik apologists keenly use the fact that a former general (Kozlovsky) was present in Kronstadt to conclude that the uprising was inherently counter-revolutionary. The Bolshevik propaganda machine used the presence of this former white general who for further context was placed in Kronstadt by Trotsky as an artillery specialist as further justification to argue that the provisional committee of Kronstadt was being funded and led by the West and Western spies. Rather than relying on Soviet archive material to justify the slaughter of workers, it is useful to read the daily bulletin (Izvestia)(8) published by the provisional committee of Kronstadt which detailed their ideas, motives and the state of Kronstadt before the Bolshevik bombs dropped. In the first issue of the Izvestia, the provisional committee who were formed after the initial conference of sailors and workers on March 2nd dismissed any claims that would be made later by the Bolsheviks by stating their aims as follows: “Comrades and citizens! The Provisional Committee is deeply concerned that there should not be spilled a single drop of blood. It has taken emergency measures for the establishment of revolutionary order in the town and fortress, and at the forts. Comrades and citizens! Do not stop work. Workers, remain at your machines, sailors and soldiers in your units and at the forts. All Soviet workers and organizations must continue their work. The Provisional Revolutionary Committee calls all workers’ organisations, all naval and trade unions, and all naval and military units and individual citizens to give it universal support and aid. The task of the Provisional Revolutionary Committee is a general, comradely effort to organize in the town and fortress means for proper and fair elections to a new Soviet. And so, comrades, to order, to calm, to restraint, and to a new Socialist construction for the good of all labourers.” Kronstadt from day one of their resistance against Bolshevism did not have the aim to take the heads of Lenin, Trotsky, and Kalinin. Instead, the disgruntled sailors and workers wanted to work peacefully towards building a new system based on the power of the Soviets and an end to party dictatorship. This non-hostility to the Bolsheviks is clearly stated in the passage above but also through the support of the Bolshevik section of Kronstadt who threw its support behind the committee. The claim following this that there was no firm mass of soldiers behind the committee and the Kronstadt rebellion is simply false. To put it simply if there were no soldiers or sailors or workers in support of the committee then the Bolsheviks would have no issue with walking straight into Kronstadt and reaffirming control, the fact that the Sailors did not take strategic forts important to the defence of Leningrad shows their intentions clearer than words in a bulletin can. David Schaich also highlights this point by demonstrating that the former general Kozlovsky offered advice to the committee on how best to march on Leningrad which was rejected by the committee (9) What we can demonstrate from this section of this article is that similarly to other Trot groups, Socialist Appeal are committed to protecting Trotsky and Lenin from all forms of criticism by pointing to external factors and shifting the problems of the emerging USSR onto other factors like the allied blockade, the failed invasion of Poland and lack of support from the Western proletariat. Because of this Kronstadt is often glossed over and misrepresented as a Western-sponsored rebellion which took place at a crucial moment in Soviet history, as anarchists and other leftists have demonstrated this is far from the truth. The Kronstadt rebellion was the culmination of worker’s frustration and solidarity which manifested in an initially bloodless proclamation asking for a return to democracy and workers’ soviets. Whether this will be acknowledged by the UK Trot left is yet to be seen (10) (11). The role of anarchists in the civil war: One of the final points addressed in this article is the role anarchists played in the Soviets, “Many Anarchists took part in the Revolution and in the Civil War on the side of the Bolsheviks against the White reaction. They also cooperated with the new power until the rise of Stalinism. To this day, those courageous people are considered by some modern anarchists as “traitors”. Some people never learn!” The author of this nonsense does not provide a specific date to be attributed as the rise of Stalin, even if we categorise the rise of Stalin as the period from 1924 to 1929 this claim remains false. It is undeniable that leftists from the Mensheviks, Social Revolutionaries and Anarchists participated in the blossoming soviets which emerged in 1917, anarchists who were a part of Makhno’s insurgent army did at several points either join or heavily cooperate with the Red Army to fight the advancing White army. In January 1919 the Bolsheviks and the Makhnovists formally joined forces in the Red Army to push back and crush the White general Denikin. This alliance was by all means temporary between the two sides with no agreements being made concerning the autonomy of the areas under Makhnovist control in Ukraine. Throughout 1919, 1920 and 1921, the Bolsheviks continually pushed anti-Makhnovist propaganda within their press in an attempt to discredit the Makhnovists and their political reforms in occupied territories which sought to implement libertarian communist strategies and theory which strongly contrasted the authoritarian methods of the Communist Party. This attitude was reflected in the contributions made in Makhnovist congresses held in early 1919 which saw delegates reject the imposition of Bolshevik commissars and demand the introduction of Bolsheviks without any political party delegates. “The consensus of the congress was strongly anti-Bolshevik and favoured a democratic sociopolitical way of life. Most of the delegates were against the Bolsheviks and their commissars. One delegate complained: Who elected the Provisional Ukrainian Bolshevik Government: the people or the Bolshevik party? We see Bolshevik dictatorship over the left Socialist Revolutionaries and anarchists. Why do they send us commissars? We can live without them. If we needed commissars we would elect them from among ourselves.” The attempts of Denikin and Wrangel to cement white control in Ukraine prompted continual on-and-off alliances between the Bolsheviks and the Makhnovists which saw both conflict and tactical alliances to fight the whites, ultimately it was Bolshevik betrayal in late 1920 which saw Makhnovist forces become backstabbed by Bolshevik forces and ultimately removed from Ukraine by early 1921 (12). In the early half of 1920, many Anarchists were arrested by the Bolsheviks without charges. Alexander Berkman personally conducted visits to high-ranking Bolshevik officials to guarantee the end of persecution towards so-called “anarchists of ideas”, however, this did not deter the Cheka from routinely arresting anarchists as they did in July 1921 where 45 anarchists went on hunger strike in protest against wrongful arrests. This is not to say that there were no anarchists who sympathised with the Bolsheviks, Berkman in his diary encountered many so-called “Sovietsky Anarchists” (named as such due to their friendly attitude to the Bolsheviks). Despite the collaborationist nature of some anarchists, the purges continued going into the second half of 1920 and 1921 (all of which occurred before the rise of Stalin and Lenin’s death) The death of Peter Kropotkin and the subsequent refusal of the Soviet government to release Anarchist prisoners to attend the funeral is only one of several other examples of Soviet oppression of the Anarchists, by September 1921 an agreement had been struck to release some Anarchist prisoners into exile after months of continued imprisonment in Moscow at the hands of the Cheka. Throughout 1919, 1920 and 1921 the central committee (including Lenin himself) was contacted by Berkman and his comrades in a cordial attempt to allow anarchist (and other left-revolutionary) thinkers, education and ideas to be freely expressed within Soviet Russia, these attempts at securing freedom not just for anarchists went ignored by the central committee with Lenin and Trotsky uncompromising in their oppression of anarchists from Makhno, to Kronstadt to anarchist bookshops in Moscow and Kharkiv (13). Therefore, to say that Anarchists cooperated with the Bolsheviks until the rise of Stalin is sheer nonsense, the clear lack of research and historical understanding is characteristic of Soviet apologists who refuse to accept the wrongdoings of the Bolsheviks which they seek to idolise daily (14). Alan Woods on Anarchism: In 2012 Alan Woods published an article on Marxism and Anarchism (15) which drew the attention of our Brazilian comrades in the group “Black Flag” who criticised Woods’s article. Here I will add my perspective as an anarchist communist student to Woods’s analysis. Woods starts by diagnosing the situation of UK capitalism in the wake of the 2008 financial crash, he correctly highlights how this event spurred major interest among left-wing ideas like anarchism and socialism due to capitalism upsetting the norms people experienced under neoliberal capitalism. Almost immediately however Woods misrepresents anarchism and our ideas: “Anarchism is appealing to many young people due to its simplicity: to reject anything and everything to do with the status quo. But upon deeper examination, there is a pervasive lack of real substance and depth of analysis in these ideas. Above all, there is very little in the way of an actually viable solution to the crisis of capitalism. After reading their material, one is inevitably left asking: “but what is to replace capitalism, and how can we make this a reality, starting from the conditions actually existing today?” Anarchism is a broad political tradition like Marxism with several different strands and currents emerging throughout our history, a core idea of anarchism as a political idea is indeed opposing the status quo (capitalism and the state) due to its oppression and exploitation of the working class. Anarchism cannot however be boiled down to simply this, if Anarchism was only a critique of the present without any strategies or visions for the future then Woods would be justified in making this critique. This however simply is not the case, anarchism has a wide range of strategies and a clear vision of what we believe an anarchist society would be like. Anarchists similarly to Marxists believe in a social revolution by the working class to displace the ruling capitalist class, methods, and strategies during the revolution and after it however are fundamentally different which I will outline later. Woods however believes that anarchist leaders want the following, “who believe that confusion, organisational amorphousness, and the absence of ideological definition are both positive and necessary.” Where he read this claim is beyond me. Anarchists to my knowledge have never advocated confusion and organisational amorphousness within our theory, in my mind this claim is little more than a way of calling anarchists naive and uninformed when it comes to the revolution. Anarchists have a wide variety of organisational methods and strategies which originate in 19th and 20th-century anarchist theory and working-class practice. The idea of organisational dualism and anarchosyndicalism (16) are two of the most prominent anarchist ideas about organisations and education both before and after the revolution. Having an unorganised and uneducated working class who accept their position within a capitalist society is not sufficient to overthrow capitalism. Woods is correct when he argues that organisation is necessary to stop revolution from fizzling out. Drawing on the rich history of Marxism which Woods seeks to defend we can see the type of organisation Leninists favour and its failure to assist the working class in overthrowing capitalism. To do this it is necessary to look at Woods’s chapter titled “Do we need a leadership?” Leadership: Woods’ argument about leadership and organisation can be summed up as follows, anarchists reject leaders because we don’t like them and it is not enough just to dislike and reject something without offering appropriate solutions for the future society. He then proceeds to argue that “We stand for the revolutionary transformation of society. The objective conditions for such a transformation are more than ripe. We firmly believe that the working class is equipped for such a task.” Woods demonstrates the shortcomings of current forms of working-class organisations by using examples of trade union bureaucracy and reformist political parties which anarcho-syndicalists have analysed in depth over the last century. Woods is correct when he argues that without organisation we can achieve nothing, this is not something anarchists would dispute. What anarchists would and have taken issue with is the Marxist insistence on the formation of a worker’s party and the transforming of unions into revolutionary unions. As Woods correctly highlights the current TUC trade unions that are affiliated with the Labour Party have been a major force in crushing rank-and-file militancy within the unions and acting as a very effective policeman for capital. In my own experience as a student, I have seen first-hand the role the UCU bureaucracy has had in calling off strikes at the first hint of negotiations being possible which handily lost my university teachers their fight for improved working conditions and restoration of pay – a prime example of a day to day struggle crushed by endless union management and an intense desire to return to normal (17). However, reforming unions is not a task the working class should waste their time undertaking. Unlike the 19th century when union organisers and the working class faced fierce repression, in the 21st century workers have enough freedom and organisational capacity to take the initiative and voluntarily associate to form new syndicalist unions with anarchists organised according to organisational dualism within and outside the union. If we agree with the assumption that unions at present have two roles; associational and representative, then it is clear to us that the latter function is at fault for unions corrupting and becoming servants of capital. To maintain their power, unions in the 19th and 20th centuries began to establish fixed incentives to fix their membership levels as high as possible to project influence at the negotiating table and counterbalance employers. The paying of fixed membership dues allowed for the recruitment of full-time union organisers who paved the way for the union bureaucratisation we have seen in the 20th and 21st centuries, as a result, unions have devolved from associations of workers to representative mediators for the state and capital. As Woods eluded, this development within unions has benefitted the state. The Solidarity Federation highlights the example of a reporter who asked a boss of a multinational corporation why he accepted unions in his workforce, his answer was “Have you ever tried negotiating a football field full of militant angry workers?” (18). The integration of the unions into capitalism has served its purpose in curtailing radical rank-and-file union members which in turn allows for capitalists to continually expand profits at the expense of the conditions of the worker. The same phenomenon however can similarly be applied to the Leninist workers’ party which is the favoured tool for organising a mass workers movement to end capitalism. Modern Trots and Leninists will argue consistently for the creation of a workers’ party to organise the working class and spread propaganda to prepare for the coming revolution. The main justification for centralising all power within one party comes down to the argument that without the enlightened leadership of the Marxist academics and intellectuals, the workers will not be capable of overthrowing capitalism. Revolutionary parties have sprung up under many different organisations and leaders, arguably the most relevant example for the British left today is the SWP (Socialist Workers Party) whose influence in protest movements is still as strong as ever alongside their flagship propaganda event “Marxism”. What unites them however is still a keen desire to build their parties even under immense pressure from the ruling class as argued by John Molyneux in the SWP’s journal International Socialism (19). As countless anarchists before me have demonstrated, the centralisation of power and the imposition of a new ruling class and bureaucracy naturally come full circle back towards some form of state capitalism enforced at the barrel of a gun pointed by a party commissar. As well as this not only have Marxists been adept at mishandling revolutionary moments, their policy towards industrial action in Western Europe during the 1960s and 1970s proves their ideas towards organisation as unfitting. We can see this through the Italian and French Marxists cooperating with unions to defeat and settle the strike movements in their respective nations (20) (21). In contrast to this, anarchist methods of organisation differ significantly. In the 19th and 20th centuries as mentioned previously, anarchists developed the idea of organisational dualism as a pillar of anarchist organising. Unlike Wood’s idea of using the revolutionary party as the mechanism to teach theory (generalised lessons from the past), anarchists favour creating a mass workers’ organisation spanning millions of workers from different sectors united by their shared economic and class interests whilst within this organisation there should be another one composed of anarchists who follow a specifically anarchist programme united by the principles of theoretical unity, tactical unity, federalism and collective responsibility. Although this idea was formalised in the text “The Organisational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (draft)” (22) anarchists had practised this idea since the mid-19th century in the form of trade unions with anarchist organisations which operate within and outside the union. The platform is distinct from Marxist forms of organisation due to the principles which it adheres to. If platformism was simply a set of principles to which workers subscribe then this would be no different to the programmes of Marxist workers’ parties like the SPD (23) or the programme adopted by the French Workers Party (24) (written by Marx). There is within these ideas a degree of spontaneity, unlike the regimented and stifling decision-making of parties like the SWP within their party councils. I believe organisations must lack central leadership and military-like discipline in favour of adaptability and investment within democratic processes. What do I mean by this? In the Russian Revolution for example, if given a choice between working with Makhnovists in their liberated Ukrainian territory or working in Soviet industry and under the militarisation of labour policy it seems comically obvious which one you would pick. Although the material situation is far from desirable in both examples, most revolutionaries I would argue would be heavily invested in the libertarian socialist organisations developed under the Makhnovists due to the attempts by their forces to encourage workers to take control over their production and decision-making, which adds a level of personal involvement in decision making. Contrast this to the soul-crushing levels of discipline and obedience we saw under the rule of Lenin and Trotsky, rule by decree and enforcement by political commissars not selected by yourself and your comrades is hardly a motivating factor to increase your output in your chosen (or assigned) trade. Woods expresses this idea of Bolshevik authoritarianism by referring to Marx’s idea of the “Semi-state”. Anyone who reads into the Bolshevik usurping of the Soviets can realise that this so-called semi-state is hardly an expression of revolutionary working-class power but rather the expression of Lenin’s brutal authoritarianism. Only by unifying your means and your ends within your organisations and educational efforts a true path to achieving the same end Marxists hold so dear. Revolutionary theory: I, as an anarchist communist, would like to believe that both Marxists and anarchists believe theory to be of great importance to our revolutionary class struggle. Anarchist theory and its development I believe is rooted in the practices which emerged out of working class practice in the 19th and 20th centuries. This is why anarchist theory evolves and why new theory emerges to address and detail new issues which emerge in capitalism, although I would still seek to argue that most past anarchist theory still holds some if not lots of major relevance in contemporary society. In terms of how Woods views the role of theory and Marxism, he argues the following: “Marxists base themselves on the lessons of the past. We can say what has worked and what hasn’t and apply this knowledge to the present situation. We will still make some mistakes, and it is not as simple as looking up the answer in a revolutionary cookbook, but we really have no need to reinvent the wheel; it was invented a very long time ago!” It is very easy for anyone with a limited understanding of the Russian Revolution and contemporary British leftist politics to laugh this point off by arguing that groups like the SWP and Woods’s very own Socialist Appeal still repeat the Marxist Leninist failures of the past, but that is not the point of this critique. Earlier in the article Woods makes what I believe to be a subtle dig at the way anarchists view theory: “Yet there are some who deride the very notion of theory. “We do not need outmoded political theories!” they say. “We are engaged in a great experiment and we will improvise and evolve our ideas as we go along.” These words, superficially appealing, conceal a profound contradiction.” Although in this quote he may not be referring to anarchists I believe it is important to clarify the role of theory within anarchism. Put simply anarchists do not reject theory, there are plenty of anarchist theorists ranging from Kropotkin to Shusui who have written theory, and one of the key differences between how Marxists and anarchists view theory is the way it is practiced. As mentioned previously the unity of means and ends is vital to anarchists, if we fail to practice the theory which we preach then we are arguably no better than the Trots we seek to discredit. There is little else to say on this matter, the idea that anarchists reject the role of theory and learning from the past is simply delusional thinking and demonstrates a clear lack of understanding from Woods. New anarchist theory often emerges off the back of major revolutionary upheavals like the Russian Revolution. Makhno for example developed with other Russian exiled anarchists the core principles which he believed any general union of anarchists should follow. This theory was subsequently based on the lessons learned by Makhno in Ukraine where a lack of organisation led in part to the defeat of Russian anarchism. The extent to which historical theory can be applied to our modern-day circumstances is debatable, modern anarchists all over the world and in the UK pursue strategy in the way which suits their needs the best according to the conditions in which they operate. Rather than adopting the continual Marxist strategy of building a revolutionary party in the same manner in each nation, it is down to the anarchists themselves to review their situation and proceed accordingly without defaulting to the sacred Marxist texts which underpin their values (25). Addressing theory and practice: Woods in his section titled “The Theory and Practice of Anarchism” seeks to highlight the flaws in anarchist theory and practice by analysing the question of state power and demonstrating the failure of French anarcho-syndicalists to use the general strike in 1914 (26). The question of state power, contrary to what Woods asserts is of great importance to anarchists and it forms a large part of why we are anti-statists. Woods presents the example of a general strike which brings industry to a halt, he argues that without seizing state power the capitalists can effectively starve the workers back to work. The state within Marxist political theory is not seen necessarily by Marxists as an inherently oppressive structure which is why Marxists argue that the workers once they are in control of the state can exercise its power for the benefit of the workers. As is stated countless times in anarchist theory, the state is not a neutral vessel which can be occupied and used by any class which finds itself in a dominant position. The state is a social structure which develops over time through the use of professionally organised violence, through this violence the state develops a territorial concentration and centralises functions within the ruling class (this includes legislative and judicial functions) As a result by participating within the state, any potential new rulers will have to engage in social conditions which in turn transform them over time. By becoming the ruling class of a state, workers would engage in governing, legislating, and managing. Over time these conditions will reproduce themselves via the same people whose intention was to destroy them, countless anarchists have analysed this idea and better detail than I ever could but the point still stands nonetheless (27). To achieve communism, anarchists should not engage with the state, communism is to be achieved by workers engaging in practices and social conditions which constantly reproduce libertarian communism. In other words, practice what you preach, by practising fascistic methods and forms of organisation you will in turn get fascism, by organising collectively and allowing the worker to feel that he or she is driving the revolution you will create anarchy. Kropotkin in “The Conquest of Bread” said that during revolutionary upheaval the workers must expropriate industry to immediately guarantee people’s basic human needs (food, housing, and clothing). This process is not to take place while the workers stand around during a general strike as Woods seems to think, instead, the process of the expropriation of industry and agriculture should be an immediate priority of workers and anarchists to prevent capitalists from starving workers into submission. The CNT-FAI for example after the July 1936 revolution immediately went about seizing and collectivising industry, agriculture and the means of communication and distribution within Catalonia which was followed by the removal of bosses and the public ownership of the means of travel in Barcelona. Following on from this, Woods points out how the CGT in France abandoned its anarcho-syndicalism when it failed to seize state power before World War I which was followed by the union backing the French war effort. It is easy for both sides to pick out examples which benefit their analysis. I, for example, could argue that the SPD backing the German war effort in World War I demonstrate the failure of Marxist parties to effectively seize state power in Germany despite their intentions, but this tit for tat arguing serves little purpose overall. The general strike as a tool anarchists can use to paralyse and ultimately destroy the state is a powerful weapon but as Woods criticised it, it alone it cannot be successful, Woods seems to imply throughout his analysis that anarchist militants would simply stand around while on the general strike while capitalists proceed to walk all over them. This is by no means true, revolution and the general strike is a period of industrial action and militant action by the workers in defence of their comrades against the state’s oppression. As a result, anarchists and workers do not view the general strike as something to conduct and simply leave, it is one of several actions anarchists need to take to achieve libertarian communism after the downfall of capitalism. The final stretch: Woods finishes with a series of points about the anarchist insistence on majority voting as well as a passionate defence of Lenin and workers’ control and the need for revolutionary violence to achieve peace. As I have done multiple times before I would refer the reader to Maurice Brinton’s work titled “The Bolsheviks and Workers Control” for the best critique of Lenin and his failure in the revolution to uphold and defend workers’ democracy and control. Throughout Woods’s analysis of anarchism, he is prone to making incredibly shallow points which seek to mischaracterise anarchism as a naive political theory which is bound to fail due to its tendencies to create bureaucracy, its reluctance to seize state power etc. I would argue this piece is little more than Bolshevik apologism as well as a vague jab at a fictional anarchism Woods has drafted to pass us off as uninformed. In terms of majority voting anarchists have a mixed history with the concept, in an ideal situation achieving consensus is by all means desirable but in most situations it is not always achievable especially when trying to cooperate on the left with other non-anarchist groups. Throughout history anarchists have advocated for and used majority voting as well as unanimous agreement, Malatesta throughout his life advocated for the use of majority voting as well as unanimous agreement depending on the context. If achieving consensus is deemed impossible by default Malatesta argued that majority voting or third-party arbitration should be defaulted to. Anarchists also do not tend to believe in voting on every single issue which emerges in society, in both revolutionary upheaval and anarchy itself fewer and fewer decisions will have to be made once the optimal solution for an issue is decided or established (28). It would therefore be a waste of time for anarchists to engage in voting on what time of year farmers should plant their crops as through centuries of experience farmers have already established appropriate means of doing so. In instances where majority voting is used in a congress or general assembly, it is still nonetheless important to give a platform to the minority as well as the resources to test their ideas so that over time they may become the majority opinion. Rather than having a universally binding and paralysing programme within a party, I would argue it is ideal to strive for consensus where possible while simultaneously recognising the need to adopt majority voting when this cannot be achieved. Revolutionary violence on the other hand is necessary for the defence of revolutionary gains, I believe very few on the left reject this idea. However, as Alexander Berkman (29) argued we cannot equate periods of revolutionary violence with the revolution itself as the two are vastly different. The revolution is not simply burning down parliament and Whitehall and declaring victory for the people, this period of violence is by all means transitionary and defensive. What is known as the revolution is everything that comes after, the reconstructing of society, the building of new social values and relations fitting of our vision for our future society, this idea of the revolution does not emerge out of the barrel of a gun but rather out of the energy of the people who conduct the revolution itself. We cannot therefore equate a revolution simply with violence, to do so is to discredit what we are trying to achieve in the long term (Libertarian Communism) Rather than relying on Reddit testimonies and outdated practices preached by British Trots, anarchists must formulate coherent answers to the lies and misleading propaganda of groups like Socialist Appeal. Without reinforcing our ideas in our organisations, we run the risk of losing more and more comrades to the forces of the Trotskyist left which further distances us from our goal of libertarian communism. By applying our historical theory to our present day, we can and must create the necessary organisations and bodies to help anarchists carry out the social revolution. Jacob Dawson, 23 December 2023 (1)www.marxist.com/ (2)Mason, Rowena (2021) Labour votes to ban four far-left factions that supported Corbyn’s leadership (3)revolutionfestival.co.uk/ (4)socialist.net/programme/ (5) Kramer, A. (2003) Kronstadt: Trotsky was right! New material from Soviet archives confirms the Bolsheviks’ position. (6) Brinton, Maurice. (1970) The Bolsheviks and Workers Control. (7) From now on I will use SA and Socialist Appeal interchangeably. (8)libcom.org/article/kronstadt-izvestia (9) Schaich, David (2005) Kronstadt 1921: An analysis of Bolshevik propaganda, libcom.org/article/kronstadt-1921-analysis-bolshevik-propaganda-david-schaich (10) Kalyonov, Andrey., Gigantion, Byran. (2021) Who Were the Kronstadt Rebels? A Russian Anarchist Perspective on the Uprising. (11) Berkman, Alexander (1922) The Kronstadt Rebellion. (12)Palij, Maichael. (1976) The Anarchism of Nestor Makhno, 1918-1921. (13) Heath, Nick. “Anarchism, Russia.” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, edited by Immanuel Ness, 141–143. Vol. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. (14) The Anarchist Library has many great pieces about the role of the Bolsheviks and Anarchists within the Russian Revolution, I would recommend reading further into the matter as I cannot offer an extensive account of the revolution itself – theanarchistlibrary.org/category/topic/russian-revolution (15) Woods, Alan (2012) Marxism and Anarchism. (16) Rocker, Rudolf (1938) Anarcho-Syndicalism: Theory and Practice. (17) Topple, Steve (2023) The UCU cancelling strikes has thrown up questions about the union. (18) Solidarity Federation, (2012) Fighting for ourselves, Anarcho Syndicalism And The Class Struggle, pg 19, chapter 1. (19) Molyneux, John (2019) In defence of party building, International Socialism, Issue 163, isj.org.uk/issue-163/. (20) Cohn-Bendit, Daniel, Cohn-Bendit Gabriel (1968) Obsolete Communism: The Left Wing Alternative. libcom.org/article/france-1968-reading-guide (21)Lowry, Sam (2008) Worker and student struggles in Italy, 1962-1973. libcom.org/article/worker-and-student-struggles-italy-1962-1973-sam-lowry (22) Dielo Truda (1926) Organisational Platform of the Libertarian Communists. (23) Protokoll des Parteitages der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands: Abgehalten zu Erfurt vom 14. bis 20. Oktober 1891 [Minutes of the Party Congress of the Social Democratic Party of Germany: Held in Erfurt from October 14-October 20, 1891]. Berlin, 1891, pp. 3-6; www.marxists.org/history/international/social-democracy/1891/erfurt-program.htm (24) Marx, Karl (1880) The Programme of the Parti Ouvrier. (25) All pictures used in this article can be credited to the International Institute of Social History – search.iisg.amsterdam/ (26)To quickly address his criticism of Bakunin, yes he was very anti-Semitic and this needs to be shunned and condemned in every way possible. (27) Baker, Zoe (2019) Means and Ends: The Anarchist Critique of Seizing State Power. (28) Malatesta, Errico (1884) A Dialogue On Anarchy. theanarchistlibrary.org/library/errico-malatesta-between-peasants (29) Berkman, Alexander (1929) What is Communist Anarchism? theanarchistlibrary.org/library/alexander-berkman-what-is-communist-anarchism After an extended break from publishing articles and pieces from RAG members we hope to begin publishing pieces soon here on our website. Watch this space for articles and blog entries going forward!

In solidarity, Jacob RAG The last few months have seen several strikes and industrial actions across the Birmingham area, including a Work to Rule by Birmingham City Council bin workers, ongoing strikes by home care workers in dispute again with the City Council and an autonomous strike by Deliveroo riders.

Bin Workers with Unite the Union originally went on strike in June 2017, winning popular support across the city, while GMB workers remained at work over the same period. After the three months the dispute was resolved. However, in the months since, it has been revealed that GMB workers were given a payment of around £4000 each over this period, purportedly as compensation for an error in protocol during negotiations between the council and GMB. Unite members claim that this was a payment made in discrimination against the striking workers. The workers voted almost unanimously in favour of action short of a strike, opting for a Work to Rule (where workers refuse to work overtime or perform any tasks which are not specified in the contract of employment). The Work to Rule lasted around 3 months, before the dispute was resolved at the end of March during a meeting with Birmingham City Council. Things started to go wrong when workers in GMB and Unite did not manage to stay united in their response to the job losses which spawned the strike back in 2017. In periods of high union struggle, workers would strike together across industries and workplaces (a tactic called solidarity action or 'sympathy striking'), a practice now outlawed due to its power in the fight against the ruling class. Workers must stick together in their battles against bosses, landlords and governments, because solidarity is our greatest strength, while division is the favoured strategy of the ruling class. Care workers are continuing strike action started 18 months ago in response to proposed changes to working patterns which could lead to wage cuts of up to £4100 and unworkable split-shifts which would effectively force many out of the job. The dispute has stretched to 70 days of strike action so far, with workers changing tactics since the new year, flyering houses in Birmingham wards to raise awareness of the strikes and gain public support for a fair resolution to their dispute. Care workers were blocked in their collective delivery of a card addressed to 'Scrooges' at the Council House last Christmas, admirably attempting to force entry to the council building in defiance of a last minute lockout ordered by council members. RAG whole-heartedly applaud care workers for their bravery in confronting council security, who slammed the doors of the council building in their face as they sought to highlight the administrators' attacks on their livelihoods and those of their families. The same Labour councillors shamefully awarded themselves pay raises of over £600 a few months later, in April of this year. (You can donate to the Care Workers Strike Support Fund by clicking here). Deliveroo moped and motorcycle drivers also took strike action this year, in response to imposed changes away from flexible work towards a system of booked shifts. With competition for shifts high, work now needs to be booked a week in advance, a change that has effectively left many riders out of work. Workers took action autonomously, being unaligned to any formal trade union. This kind of self-organisation is brave and admirable, and we hope that we will have the opportunity to support them, alongside other cycle couriers, in future action against super-exploiters Deliveroo and Uber-Eats. Trade Union struggle is inherently limited as a form of revolutionary struggle, constraining its demands to a better form of Capitalism for unionised workers. That said, RAG support all Workers in their fight for better pay and conditions, only hoping that union struggles become more generalised, breaking free of the legal and bureaucratic limitations of union activity. It is vital that the working-class gain confidence through battles with their exploiters, to understand for themselves the contradictions of the Capitalist system of production and the opposing interests of Workers and the ruling class. If you are having trouble in your workplace, or want to understand how Workers can fight to achieve a better society, get in touch online or come and say hello at one of our open events. In 1840 the anarchist Pierre Joseph Proudhon, wrote a book called ‘What is Property?’ in which he said ‘Property is theft’, a phrase that has intrigued and inspired many political thinkers, radicals and activists.

Property takes many forms and types: The unifying form of property is one of the most basic and essential of all human rights; the need for shelter. We all seek a roof over our heads and a safe place to sleep and rest. The unfunny truth is that for the greater part of human evolution, this wasn’t a problem; people lived in familial and communal groups in which support and resources were abundant. Things started to go bad in the early growth of capitalism, when property ownership became a pivotal tool in the exploitation of the new ‘working class’. Only the very wealthy owned property, which greedy new industrialists rack-rented to their workers, but only as long as they were able to work. Once they couldn’t, they were cast off into the gutter like rubbish. It’s shocking and outrageous that the realities of life haven’t changed that much isn’t it? The great postwar dream of the ‘welfare state’ with homes and healthcare for all is just that, a dream, being sucked dry by the wealthy elite. Most younger people can’t afford the deposit on a home, so are forced to rent, lining the pockets of fat-cat landlords. Even for people who can get a mortgage, it’s the bankers that really own the building, not them. Meanwhile, large numbers of buildings big enough to house several families languish empty in our cities as plaything investments of the super rich. I’m angry and appalled by the ever growing numbers of hungry and homeless faces I see on the streets of Birmingham. I think community is more important than property. No one owns the world, it’s a gift we all share. I’m reaching out and working together with like-minded people, we’re fighting back and organising for a better future - You can too. As far back as Kropotkin and Bakunin, Anarchists have known that the potential to build a better society lies in the hands and minds of ordinary people, with little time for prescriptive dogmatism, or self appointed “great men” vying to lead the way.

In “The Conquest of Bread” (which, admittedly, if we anarchists were interested in adopting one sacred manifesto, would surely make the shortlist...), Peter Kropotkin writes of the importance, come revolution time, of ensuring the “theorists ... have no authority, no power.” Rather, he describes how, once freed from the stifling authority of government, landlords and the wage system, the working class are more than capable of organising themselves into communities in which everyone is amply fed, clothed and housed. In fact, he argues that not only is this a real possibility (as demonstrated by reams of farming statistics – some parts of the book are a little dry) but is the natural and even inevitable tendency of free people. And damn if that isn’t refreshing! There’s a contagious optimism to Kropotkin’s belief that, far from being a utopian pipe dream, anarchist communism is the obvious next step in the evolution of human society. In view of this, the book doesn’t dwell much on the mechanics of revolution, except to note most importantly that the first concern should be providing for people’s immediate needs (the titular bread) rather than, say, as in Kropotkin’s scathing example, forming committees to discuss “middle-class ideas.” The main thrust of the book, then, is that all human production is the product of an interconnected web of many people’s labour, and is enough to meet everybody’s needs. The conclusion this leads us to can be summed up in Kropotkin’s own words: “What we proclaim is the right to well-being: well-being for all!”. A call met by Anarchists across the globe to this very day. To investigate Anarchist ideas and books such as The Conquest of Bread, come the Revolutionary Anarchist Group Radical book club, 7pm on the first Tuesday of every month at the Prince of Wales in Moseley. Check out our Facebook to find out about this months book and other upcoming RAG events. With 300,000 people taking to the streets across France in November of last year, the Gilets Jaunes have maintained their struggle in to the spring of 2019. Started as a response to an increase in fuel tax, the yellow-vested protesters have blockaded roads and fuel depots and been subject to considerable police violence.